The junk-wax era is usually treated as a punchline. Overproduction, endless supply, and binders full of cards that “aren’t worth anything.” And yet, if you look closely enough, this is exactly where some of the best value plays in modern collecting quietly live.

Not because these cards are rare.

Not because they’re the most valuable.

But because they represent the right version of a player at a price that still makes sense.

Often, a junk-wax rookie isn’t the top of the market — it’s the correction.

The Value Thesis

Junk-wax rookies work when they meet three conditions:

- They capture the player at the moment that matters

- They’re recognizable and culturally anchored

- They’re priced for reality, not narrative

When those line up, you get cards that may never headline an auction, but quietly outperform expectations over time.

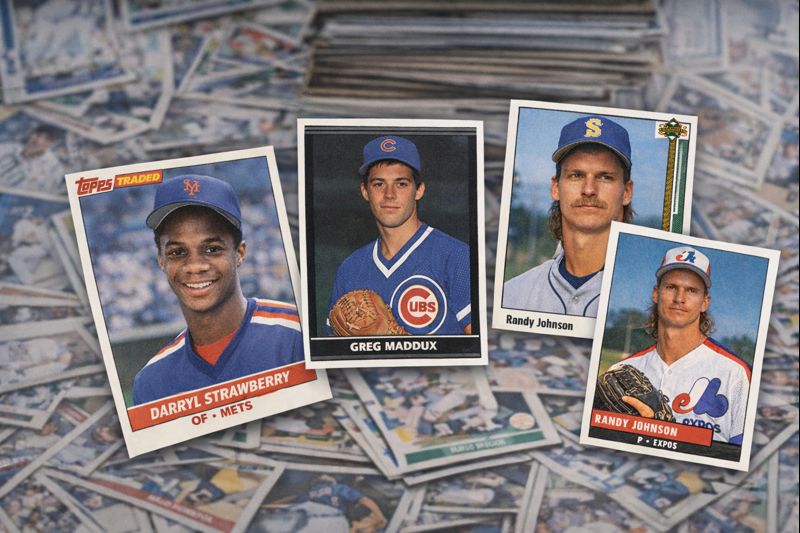

Case Study #1: Darryl Strawberry — When Arrival Matters

Strawberry is where the thesis is cleanest.

His 1984 rookie run still offers absurd value:

- 1984 Topps around $5

- 1984 Fleer and O-Pee-Chee around $15

- 1984 Donruss at $25, fair and defensible

- 1983 Topps Traded around $55, still a legitimate value play

None of these are compromises. They’re iconic, early, and tied to the uniform and era people actually care about.

Where the comparison gets interesting is what comes after.

A 1993 Finest Refractor pushing $150+ in a PSA 8 isn’t priced that way because it represents Strawberry at his best. It’s priced because it’s shiny, condition-sensitive, and difficult to replace. Likewise, something like the 1997 Topps Gallery Darryl Strawberry Player’s Private Issue may never surface at any price — but rarity alone doesn’t create meaning.

This is the core distinction:

Scarcity without context isn’t value. It’s trivia.

In Strawberry’s case, the early cards tell the story that matters. Later cards may be rarer, but they’re detached from accomplishment.

Here, the junk-wax rookie isn’t the fallback — it’s the anchor.

Case Study #2: Greg Maddux — When Difficulty Creates Value

Maddux is the rare example where a junk-wax rookie succeeds for a different reason.

The 1987 Leaf is a steal at $15 and still fair at $20. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t rely on gimmicks. But it is black-bordered, genuinely condition-sensitive, and meaningfully scarcer than his other mainstream rookie cards.

That scarcity isn’t manufactured — it’s structural.

Corners matter. Centering matters. Survivability matters.

Maddux has plenty of cards that cost more, but many of them are priced for format, finish, or parallel math rather than for what defines his career. The Leaf works because it rewards care, not speculation.

This is the ideal junk-wax value profile:

- Early

- Honest

- Difficult for the right reasons

Not every black-border card deserves a premium — but when difficulty aligns with relevance, the market eventually notices.

Where the Thesis Breaks: Randy Johnson — When Supply Overwhelms Story

Randy Johnson is the counterexample — and an important one.

He arrived at absolute peak junk wax, when production was so extreme that even “key” rookies struggle to separate themselves. I’ve assembled a pile of 100 Randy Johnson rookies, made up mostly of what are generally considered his two best:

- 1989 Upper Deck

- 1989 Topps Traded (call it an XRC if you want — it doesn’t matter here)

They’re iconic. They’re correct. And they’re effectively interchangeable.

This is where the value math flips.

From a real-world spending standpoint — not price guides — you’re often better served skipping the rookies entirely and moving slightly later. Cards like 1990 Leaf Randy Johnson routinely outpace those rookies in what you actually end up paying. Demand concentrates there. Sellers hold firmer. Discounts disappear faster.

Because Johnson’s greatness wasn’t immediate.

His legacy was built later — when velocity met control, and dominance became sustained.

This is the danger zone for value collectors: when supply is effectively infinite and the player’s defining years come later, even “the right rookie” stops being special. Ownership loses friction. You can always get another one.

Here, the rookie isn’t the anchor — it’s inventory.

There’s an obvious footnote here: the 1989 Fleer Marlboro error. The market has decided that partially obscured ad variants matter. I don’t agree. If the distinction requires a guide, a light source, or an explanation to even see, it isn’t adding value to the card or the story. That’s classification-driven scarcity — trivia, not substance — and it doesn’t change the underlying math. It doesn’t make the rookie scarcer in any meaningful way, and it doesn’t move the moment closer to Johnson’s actual legacy.

In peak junk wax, potential is cheap.

Inevitability costs more.

The Framework, Refined

So yes — junk-wax rookies often become the value play.

But only when:

- Arrival matters more than ascension

- Difficulty is real, not cosmetic

- The card represents the version of the player people actually remember

When those conditions fail, the smarter buy may be the moment — not the debut.

The Takeaway

The goal isn’t to buy the cheapest card.

It’s to buy the most honest one.

Sometimes that’s a rookie.

Sometimes it isn’t.

But when a $15–$55 junk-wax card is being cross-shopped against $150 parallels or cards that may never surface, the rookie isn’t the compromise.

It’s the correction.

Leave a comment